![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

'Deeds' of Experience

Santa Cruz poet Gary Young takes a page from William Blake in his newest work

By Morton Marcus

IT MAY SEEM preposterous at first to compare Gary Young to William Blake, but the elements of both men's careers are so similar that once they are pointed out, the comparison seems obvious. Blake was a master printer and publisher. So is Young. Blake was a poet. So is Young. Blake illustrated and designed his own books in revolutionary layouts. Again, so does Young. And now with the publication of his fourth book, Braver Deeds, Young, it is clear, has embarked on an endeavor that brings him even closer to his immortal forebear.

Blake's first important work was a two-part project called Songs of Innocence and Experience. Songs of Innocence appeared first, and several years later was joined by Songs of Experience. Together, the books defined the essential dichotomy that underlies human experience as Blake saw it.

The books contain matching poems, the most telling being "The Lamb" of Innocence and "The Tiger" of Experience. As can be imagined just from the titles of these poems, Songs of Innocence depicts a bucolic, childlike picture of the world, and Songs of Experience an adult view of the bitter reality of failed dreams and political and psychological repressions to which humans are heir as grow-ups.

Two years ago, Young published Days, a sunny, almost pastoral vision of the world, a gentle book of days to accompany his new son through infancy and youth. To be sure, there are pieces in the book that address the harsher realities, but generally the volume is Young's Songs of Innocence. The Blake comparison continues, because even though Young didn't publish Days himself, he was allowed to design the book and illustrate the cover.

Now Braver Deeds appears, the winner of this year's Peregrine Smith Poetry Prize, and once again Young has been allowed to design the book and illustrate the cover. Interestingly, the cover matches the pastoral illustration of Days in style and color, although a preponderance of grim grays replaces the sunny yellows of the earlier volume, a fitting change, since Braver Deeds is Young's Songs of Experience and explores the dark side of human experience.

If Days was concerned with birth, growth and discovery, Braver Deeds focuses on death, mental and physical illness, the crimes we perpetrate on each other--and how our meeting these crises, both as children and as adults, in many cases shows us to be, if not heroes, the enactors of a daily bravery worthy of homage. It is that praiseworthiness that turns the grim events recounted in the volume into a rejuvenating experience for the reader that in the end is uplifting.

Braver Deeds deals directly with the lives we lead. One of Young's major accomplishments in the volume is that as personal as many of the poems are, one comes away from each page with the conviction that Young is speaking about the reader's life as much as about his own. When all is said and done, Young has refused to allow himself to wallow in self-pity but has entered our lives in a communal act of compassion, a sort of laying on of words, to either heal us or at least ease the pain of our mortal journey.

Each poem in Braver Deeds has its own power, but as one poem joins another they gather a cumulative energy that grows like a slowly building thunderstorm. By the end of the book, the reader may well feel, as I did, that he has confronted his life and endured.

IT IS IN THEIR poetic approaches that the comparison between Blake and Young breaks down. Blake employed the medieval English ballad as his basic form in Songs of Innocence and Experience, whereas in both Days and Braver Deeds, Young uses a radical form of prose poem all his own. All the pieces in Braver Deeds are composed of single paragraphs usually comprising three to five sentences. Within this confining form, Young is able to evoke meanings that it would take other poets pages to suggest.

And how does Young resolve the loss of the poetic line as his basis of rhythm and tension? He transfers those elements to the sentence, using the sentence as his basic rhythmic unit, playing long sentences off against short ones. All his sentences, however, are so packed with evocative details and so stringently condensed that they resemble that supreme carrier of information and suggestive detail, the haiku at its most efficient.

Let me explain that last statement. In many ways, the 17-syllable haiku is the essence of poetry, since it implies meanings and evokes experiences in the fewest amount of words. The art of poetry is found in the poet's ability to condense and through this brevity of expression to suggest volumes of meaning. It is this essential element of poetry that Young has transferred to the prose poem with a mastery that again reminds me of Blake but with an evocative power that goes beyond the old poet.

Blake, you see, was locked into a narrow vision that he was always, for want of a better word, propagandizing. Young, however, evokes a wide range of feelings and ideas on various subjects in each of his poems. This multidimensional approach resembles the ripple effect the proverbial rock sets off when it splashes through the surface of a pond. I call this effect the "resonances" (that is, the continuation and simultaneity of meanings) that arise or emanate from a successful poem.

Let me illustrate what I'm talking about by looking at how several poems from Braver Deeds work.

I've always thought that a poet, whether aware of it or not, aimed either to achieve insight or to evoke vision, although both can be achieved in the same poem. The poem of insight provides interpretations for individual actions we undertake and/or the events that befall us. The poem of vision, on the other hand, attempts to evoke a sense of overall purpose for human acts and to provide the meanings that underlie the workings of the universe.

Young writes the poem of insight. Grounded in our everyday world, he grapples with the meanings behind our actions by bringing together two and sometimes three unrelated elements which through their placement together lead the reader to make meaningful connections where he/she may not have seen any before. The method's power is achieved by implying a meaning between the elements through their juxtaposition.

Another way of explaining this method is to say that the juxtaposition of different elements "implies" a comparison between them, but the comparison is never overtly stated. Therefore it is not surprising to find a paucity of metaphors and similes in Braver Deeds, which gives the reader the impression that the book is made up entirely of declarative sentences that have the authenticity of news items from the daily paper.

The method is clearly at work in "I Had a Friend," in which the speaker tells of a boyhood friend who later was killed in a hunting accident. The speaker then talks about seeing one of the many "massacres" we are all too often exposed to on the news and remarks that for a moment he thought he knew one of the dead, implying a relationship between the private loss of his friend and the universal loss of another member of the species.

In another poem, the speaker's mother comments on the violets that her son brings her when she's confined to bed as "beautiful, but they never last," indirectly commenting on her inability to find lasting mental or physical peace. This indirection is another method Young uses to highly dramatic effect in one poem after another, as, like most of us, the characters in the book cannot confront the motivations behind their actions.

I WAS ENTRANCED by so many poems in Braver Deeds, I will not even try to list my favorites. Besides, pieces I thought weak at first blossomed after two or three readings. "Crushed by Love," for instance, is one of the most thought-provoking definitions of God's existence I've ever read.

Through these juxtapositions, indirections and direct confrontations with our most painful experiences and mental demons, Young unflinchingly records and elucidates the stuff of our daily existences. But everywhere in the book, there is a stubborn insistence on life's glory, as in the marvelous "The Doctor Said," where, after going through one medical crisis after another, the speaker can still declare, "I love this life."

In Songs of Innocence and Experience, Blake pursued the notion that the generations of humankind are locked in a cycle of birth, suffering and death that in later books he would say could only be broken by the revolutionary powers of the imagination to transform the world as well as to change our perceptions of it. His vision, in the end, is devoutly to be wished but hopelessly literary, even Romantic.

Young's vision is rooted inside the daily round of existence. It may, at this point, not have Blake's audacious sweep, but it is more realistic, more humble, and finally more heroic in pointing out the bravery with which the majority of us face our daily lives.

The Geography of Home: California's Poetry of Place, selected and edited by Christopher Buckley and Gary Young; Heyday Books; 444 pages; $16.95 paper.

Gary Young reads Thursday (June 3) at 7:30pm at Bookshop Santa Cruz, 1520 Pacific Ave., Santa Cruz. (423-0900)

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

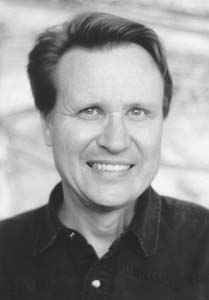

He Loves This Life: Gary Young grapples with the meanings behind our actions.

He Loves This Life: Gary Young grapples with the meanings behind our actions.

Braver Deeds by Gary Young; Gibbs Smith; 74 pages; $l0.95 paper.

From the June 2-9, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.